SERMONS IN PSALMS

|

(No. 1652) Psalms 119:54

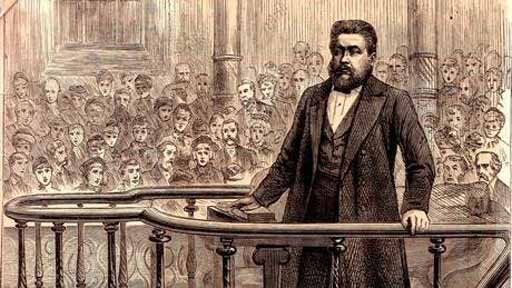

REV. C. H. Spurgeon

"Thy statutes have been my songs in the house of my pilgrimage." Psalm 119:54.THE one-hundred-and-nineteenth Psalm is said by many to consist of detached sentences, and to be rather a casket of gold rings than a chain of united golden links; yet the position of this verse is somewhat remarkable, for the verse before it runs thus: "Horror hath taken hold upon me because of the wicked that forsake thy law." Most of you know for yourselves what that sentence means; for if you hear a man swear in the streets, your blood runs chill with horror; and when you think of what has been said by blasphemers against the person of our divine Lord, and against the divine truths of revelation, you are horrified that men should have had the audacity to think much less to say such wicked things against the Most High. David rightly said, "Horror hath taken hold upon me," and then he added our text; as if he would say, "I am horrified that they should break the law of God, and tread it under foot, for to me it is an intense delight: ‘Thy statutes have been my songs in the house of my pilgrimaged That which is their scorn is my song. What they count dross is gold to me. How can they treat such precious truths contemptuously?" He is horrified at the thought that what is, to him, the very soul of his life, and the life of his soul, should be to them a cast-off and a hate. Surely some connection is visible here: these rings are evidently linked to each other. It is well to notice the following verse. David writes, "I have remembered thy name, O Lord, in the night, and have kept thy law," as much as if he had said It is not always daylight with me; buy when it is, thy statutes are my song. My sun is not always above the horizon; but when it is dark with me, and I am in trouble, I do not forget thee. Thou art still my solace. I remember thy name, and I am comforted. If I may not see thy face, it is a joy to remember thy name; for they that know thy name will put their trust in thee. If I can but remember thy name when my spirits sink, I shall have my soul stayed and upheld until the daylight shall again break in upon my spirit. Is there not much sweetness in this hopeful assurance, much to make our text overflow with meaning? And now I invite you to consider the text itself. It seems to me to talk about three things, three things which concern us. The first is a pilgrim; who is, secondly, a singing pilgrim; and this brings before us, thirdly, his song-book; "thy statutes have been my songs in the house of my pilgrimage." "Sweet strains to me thy laws have been, Sweet music in my heart, Where on my lonely pilgrimage I sojourn all apart." I. First, here is A PILGRIM. David was a type of all who are true disciples of Jesus. They are all pilgrims. A pilgrim is a person who is travelling through one country to another. If we are true to our profession, we are pilgrims with an emphasis; for, first, we belong to another country. We were not born here as to our highest nature. When we were born in the most emphatic sense we were born of another country altogether; "not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, but of God." "Except a man be born again" "from above," says the margin "he cannot see the kingdom of God." We have been born from above. Our birth makes us citizens of the city which hath foundations, whose builder and maker is God. We are aliens, foreigners, strangers in this world. One said of old, "I am a stranger with thee, and a sojourner, as all my fathers were"; and another said, "I am a stranger in the earth;" indeed, all the faithful confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. Jesus, our leader, said, "Ye are not of the world, even as I am not of the world;" and the beloved disciple said, "Ye are of God, little children, and the whole world lieth in the evil one." We are hurrying through this world as through a foreign land. We are in this country, not as residents, but only as visitors, who take this country en route for glory. Ungodly men live as if they never meant to die. All their plans and preparations are evidently arranged for tarrying in this country; but if God has instructed you aright, you know assuredly that you shall die, and you have become familiar with the thought of departing from these shores. Here you have no continuing city, but are like the tent-dwelling patriarchs, who by their very abodes confessed that they looked for a possession yet to be given them. You look not only upon all other men as mortal, but upon yourselves as such; nor do you at all regret it; you would not stay here for ever if you could. You know that you are emigrants to the land of the unsetting sun, and these lands are but traversed on the road to your eternal heritage. This is a rare knowledge, peculiar to the godly. You may bring an unconverted man to be conscious of his mortality, but you cannot get him to realize that he is going to another land. Nay, he is going, he is going, he is going whither he would not. He is hurried to the land of confusion and dismay, where the shadow of death for ever rests on hopeless spirits. You do not wonder, therefore, that he tries to avoid the remembrance of this troublesome fact, and that he journeys on with his eyes shut, trying to forget that his life’s voyage will ever end. To you, dear friends, your passage through this world is not a transit to somewhere or to anywhere; for you know where you are going. As Jesus said to the disciples, "Whither I go ye know, and the way ye know": you know which way Jesus went, and you know that you will go the same way; for he has promised that where he is there you shall be also. One of his solemn declarations was, "Because I live, ye shall live also"; and one of his last prayers put this promise into the form of authority and claim "Father, I will that they also, whom thou hast given me, be with me where I am; that they may behold my glory." If an Italian now in England passes through France on his way to the Eternal City, he stays at Paris, or Lyons, or Marseilles, on his journey; but all the while he is not a Frenchman, he is an Italian. Wherever he stays upon the road, he says to himself, "This is not Rome. This is not the place of my nativity. I have no citizen rights here; I am going onward to my own dear city, and I must hasten as best I may until I reach it." That is the condition of the Christian: his face is steadfastly set to go to the New Jerusalem, and nothing must detain him. A pilgrim in the old crusading times started out to reach Jerusalem. You know how many were attacked with' that insanity in those times; I commend them not, but I use the illustration in all soberness. The Crusader journeyed on foot across Europe. Whenever he came in sight of a goodly city, whether it was Vienna, or Constantinople, he stood and gazed upon the towers, the spires, the minarets; and when he had done so, he turned to his companion and said, "A fair sight, my friend; but it is not the Holy City to which you and I are journeying." So, whenever God brings us to any place, however pleasant or delightful it may be, it is for us to say, "A fair sight, and God be thanked for it; but it is not the Golden City yet." Our gardens are not Paradise, our homes are not the Father’s house on high, our comforts are not our heaven, our halting-places are not the everlasting rest. We must not rest contented here below. We have not come to that promised land whereof God has spoken to us in his covenant. If we were mindful of the place from which we came out, truly we have had many opportunities to return; but we are not mindful of it; our whole desire lies in the opposite direction; our burgess-rights and civic privileges connect us with a city whose jewelled walls and shining streets are waiting for our coming. Our Captain cries to us, "Forward." Beyond the river our possessions lie. In another land is our everlasting abode. We are, then, pilgrims born in another country, passing through this world to an inheritance beyond. A pilgrim' s main business is to get on and pass through the land as quickly as he may. You will remember how Israel desired to pass through the land of Sihon, King of Heshbon, and Moses offered these terms "Let me pass through thy land: I will go along by the highway, I will neither turn unto the right hand nor to the left: only I will pass through on my feet." Sihon would not allow them to pass on these conditions; neither will the world grant us a similar privilege. The tribes had to fight their way, and so must we. All we ask is a road. We may also beg the loan of six feet of earth for a sepulchre, but all else we will forego if we may the better proceed towards our inheritance. Not how to stay here in comfort, but how to pass through the land in holiness is our great question. Sometimes a home sickness is upon us, and then we are weary of this wilderness, and pine for the land which floweth with milk and honey. We hear the inviting heralds and the songs of those who hold high festival in the palaces above, wherefore we groan being burdened, and long to end the days of this our banishment: "Let me go, oh speed my journey, Saints and seraphs lure away. Oh, I almost feel the raptures That belong to endless day. "Oft methinks I hear the singing That is only heard above. Let me go, oh speed my going, Let me go where all is love!" As pilgrims, it is true in our case that our relatives are not, the most of them, in this country. We have a few brethren and sisters with us who are going on pilgrimage, and we are very thankful for them; for good company cheers the way. It is pleasant when Christiana can take her dear friend Mercy with her, and when her boys Matthew and James can go, and Mr. Greatheart with them. Though, if need be, Christian must leave Christiana and all the rest behind if they will not go with him, still it is much more pleasant to see them going on pilgrimage with us. Yet the majority of those dear to us are already over yonder. If I may not say the majority by counting heads, yet certainly in weight the great majority will be found to be in the far country. Where is our Father? Where but in heaven? And where is our Elder Brother? Is he not there too, at the right hand of God? And where is the Bridegroom of our soul? the truest and best Bridegroom with whom we are joined in a marriage union, which death cannot sever? Where, I say, is the Bridegroom of our souls? We know right well. And may not the bride desire the happy period of the home-bringing the joyous marriage feast, the supper of the Lamb? Where our Father is, and where Jesus is, must needs be our own country, and we are exiles till we reach it. If we have a clear eye for spiritual relationships, see what a host of our nearest and dearest ones have gone across the river already, and are in the glory land. Multitudes, multitudes are there: Gad, a troop cometh, a host innumerable. We are come unto "the general assembly and church of the firstborn, whose names are written in heaven." Let us, therefore, go on with great speed: let us not think to tarry here, for our best friends and kindred have entered into their rest, and it becomes us to follow after them. And, you know, a man who is a pilgrim reckons that land to be his country in which he expects to remain the longest. Through the country which he traverses he makes his way with all speed; but when he gets home he abides at his leisure, for it is the end of his toil and travail. What a little part of life shall we spend on earth! When you and I have been in heaven ten thousand years we shall look back upon those sixty years we spent here as just nothing at all: their pain a pin’s prick, their gain a speck, their duration the twinkling of an eye. Even if you have to tarry eighty or ninety years in this exile, when you have been in heaven a million years the longest life will seem no greater than a thought, and you will wonder that you said the days were so weary and the nights so dreary, and that the years of sickness dragged such a weary length along. Ah me, eternal bliss, what a drop thou makest of our sea of sorrow I Heaven covers up this present grief, and so much overlaps it that we could fold up myriads of such mournings and still have garments of joy enough to clothe an army of the afflicted. We make too much of this poor life, and this fondness costs us dear. Oh for a higher estimate of the home-country, with its delights for evermore! then would the trials of a day exhale like the dew of the morning, and scarce secure an hour of sorrow. We are only here time enough to feel an April shower of pain, and we are gone among the unfading flowers of the endless May. Wherefore let us not make the most of the least, and the least of the most; but let us put things in their order, and allot to brief life its brief consideration, and to everlasting glory its weight of happy meditation. We are to dwell throughout eternity with God! Is not that our home? That is not a man’s residence into which he enters at the front door and in a moment passes out at the back, and is gone never to return, as though it were a mere passage from one street to another; and yet this is about all that believers do as to this poor world. That is a man’s home where he can sit him down at his ease and look on all around him as his own and say "Here will I make a settled rest, While others go and come, No more a stranger or a guest, But like a child at home." Yes, this shows that we are pilgrims, because we are here for so short a space compared with the length of time we shall spend in the dear country beyond. One thing that always marks us as pilgrims is this, that we are treated by the people of this land as strangers. Different races of men reveal their nationality by their speech, their dress, their manners, and their habits. That which is perfectly natural in a Dutchman seems ridiculous to a Frenchman, while the customs of a Chinaman horrify a Briton. As we who are of the hill country pass through these lowlands the people discover our foreign character, and take a wondering interest in us, sometimes of a friendly sort, but oftener of a hostile kind. They marvel whence we are, and as they cannot make us out they often come to the conclusion that we are acting a part, and are nothing better than hypocrites and pretenders. They, of course, are honest, and all who are not like them must be false and contemptible. This suspicion and ill will does not happen to all professors, but more or less it falls to the lot of all genuine Christians. They cannot be hid, and yet they cannot be understood, for their life is hid. Gladly would they pass incognito through the land, but the men of the world will not have it so. They soon discover the pilgrim strangers, and they think them very odd. I suppose they are so, if judged by the customs of the world. We do not drop into the ways and customs of the ungodly; for our Master said to us, "Have no fellowship with the unfruitful works of darkness, but rather reprove them." Hence, in this world, the true Christian is as strange as a Red Indian in Cheapside. People do not understand saints, they cannot make them out; for they are constructed upon different principles from other men, and often do things which men count foolish, unmanly, and absurd; for the laws which govern them are not such as the world esteems. Hence it happens that the ungodly forge a strange name for a Christian; they cannot make head or tail of him, and so they set him up in their chamber of horrors, and fix a nickname upon him. They declare right positively, "He is mad." Blessed madness! Another time they say, "He is a hypocrite." One cries, "It is cant"; another, "It is fanaticism." Those are all expressions by which the world shows that it cannot make us out. Are you surprised when they use such titles? You ought to be very much surprised if they do not use them. If the utterly worldly man says, "I perfectly understand you," then say to yourself, "Then I am like you, for if I had been different from you if God’s grace had given me a different way of thinking you would have been sure to find fault with me." Oh, never be afraid of the world’s censure, brethren; its praise is much more to be dreaded. When Socrates was told, "Such a man speaks well of you to-day," the philosopher was by no means gratified, but concluded that he must have done something amiss that such a fellow should speak well of him. Take censures out of a foul mouth to be your highest praise, but praises out of such mouths are worse than abuse. We are strangers, speckled birds, curious creatures, beings that are twice born, who have a new life which is an enigma to ungodly men. "The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, or whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit." He is an unaccountable person. "Thou canst not tell whence he cometh or whither he goeth." He who finds redemption and eternal life in Jesus is judged to be a strange, out-of-the-way being. He who looks for his happiness in the world to come is made thereby a pilgrim, and that is to men of this world a sort of gipsy life, fictitious, romantic, absurd, and unpractical. We who are indeed such accept our appointed condition, and the scorn which often comes with it, and henceforth we break loose from bonds of time and sense to seek another country, that is, a heavenly. "Cheerful, O Lord, at thy command I bind my sandals on; I take my pilgrim’s staff in hand, And go to seek the better land, The way thy feet have gone." II. But now, secondly, according to our text, the believer is A SINGING PILGRIM: "Thy statutes have been my songs in the house of my pilgrimage." He does not say "my song" only, but "my songs," in the plural, as if he had been a great singer, and given to singing, which proves that pilgrims to heaven are a merry sort of people after all. They have their trials, some trials more than those which other men know; but then they have their joys, and among these joys are sweet delights such as worldlings can never taste. On the whole, Moses is right in his judgment of the Lord’s people: "Happy art thou, O Israel." "Blessed are the people," says the Psalmist, "that know the joyful sound. They shall walk, O Lord, in the light of thy countenance." Holy pilgrims are happy; theirs is not the caravan of despair, but the march of those who go from strength to strength. I hear a voice objecting, "You give a rose colour to facts, for some religious people are very gloomy." I dispute not the fact. For sure some days are dark, and yet day is not the time of darkness: even noontide may be dim, and yet noon is not the hour of gloom. On earth all men must eat some bitter herbs, whether they eat the paschal lamb or not. Moreover, all are not truly godly who profess to be so. They fancied they were religious, and therefore felt themselves bound to keep up the profession: surliness and gloom are part of the buttressing by which they keep up the flimsy structure of their piety. Their religion is not real, and so they make it terrible. If your cheek is painted you know that its ruddy hue may yield to a handkerchief or to a drop of perfume, and therefore you keep your distance and appear reserved. The countryman’s rubies are not so soon dissolved; the roses of rude health are not so speedily uprooted. I have known people who painted themselves up as Christians, and they felt it incumbent upon them to look very demure, or else their paint would have come off. They thought that they must add melancholy to their profession to imitate holiness. False notion. The gloom betrays the child of darkness. "But we do measure people’s piety by the length of their faces," says one. Do you? So do I, and I like them short the shorter the better. Those who draw very long faces do it as a matter of pretence, and this is utterly to be condemned, for Jesus says that the Pharisees had such countenances that they might appear unto men to fast, but they were hypocrites to the core. Let me tell you for a certainty for I have the experience of many to back me up in it that there is a quiet, rippling rill of intense comfort in a Christian’s heart, even when he is cast down and tried, and at other times when trials are lightened there are cascades of delight, leaping cataracts of joy, whose silver spray is as pure as the flash of the fountains of Paradise. I know that there are many here who, like myself, understand what deep depression of spirit means, but yet we would not change our lot for all the mirth of fools or pomp of kings. Our joy no man taketh from us: we are singing pilgrims, though the way be rough. Amid the ashes of our pains live the sparks of our joys, ready to flame up when the breath of the Spirit sweetly blows thereon. Our latent happiness is a choicer heritage than the sinner’s riotous glee. When suffering greatly, and scarce able to stand, I was met by one who has long enjoyed rude health and unbroken prosperity. His mind is coarse, and his tongue rasps like a file, and he is ever fond of expressing his rational ideas as proof that he is a superior person. With sarcastic politeness he stood before me, and said, "Dear, dear, what a sufferer you are! But it is what may be expected, for whom the Lord loveth he chastencth." I had barely time to admit that the chastening had been severe before he added, "You are very welcome to love which shows itself in that fashion; for my part, I had rather be without it, and enjoy the use of my limbs. I can do better without your God than with him." Then the hot tears scalded my eyelids and forced themselves a passage. I could bear the pain, but I could not endure to hear my God evil spoken of. I flamed up in indignation, and I cried, "If instead of having pain in my legs I had a thousand agonies in every limb of my body I would not change places with you. I am content to take all that comes of God’s love. God and his chastening are better than the world and its delights." Truly I know it to be so. My soul has a greater inner gladness in her deep despondency than the godless have in their high foaming merriments. Yes, and even pain is tutor to praise, and teaches how to play upon all the keys of our humanity till a completer harmony comes from us than perpetual health could have produced. Was not Herbert right when he wrote of man’s double powers of grief, and then found in them double founts of praise? "But as his joys are double, So is his trouble. He hath two winters, other things but one: Both frosts and thought do nip And bite his lip; And he of all things fears two deaths alone.

Yet even the greatest griefs May be reliefs, Could he but take them right, and in their ways. Happy is he whose heart Hath found the art To turn his double pains to double praise." You that are lowest down in the scale of visible joy, you that are broken in pieces like wrecks grinding upon rocks, you that are a mass of pain and poverty you will give your Lord a good word, will you not? You will say, "Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him." At our worst we are better off than the world at its best. Godly poverty is better than unhallowed riches. Our sickness is better than the worldling’s health. Our abasement is better than the sinner’s honours. We count it better that we suffer pain like to the torture of death than that we bathe in pleasure, and that pleasure be the effect of sin. We will take God at all the discount you can put upon him, and you shall have the world and all the compound interest which you are able to get out of such a sham. God’s people sing: they are the children of the sun, birds of the morning, flowers of the day. Wisdom’s ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace. We hear a music which never ceases, full-toned and high-ascending, and its soft cadences are with us in the night when darkness thickens upon darkness, and the heart is heavily oppressed. "Sorrowful, yet always rejoicing." Know ye that paradox? Some of us have learned it now these many years. It seems that the Psalmist had times of very special delight high days and holidays; or, as the old records write, "gaudy days," days of overflowing joys. "Thy statutes have been my songs." He was not always singing at least, not at his highest pitch; but there were many brave times when he poured forth a song. If you and I cannot always sing, we do sometimes turn to that sweet amusement, and while away the time. Remember how John Bunyan represents Mr. Ready-to-Halt, Mr. Feeble-Mind, and all the rest of them: when they had cut off Giant Despair’s head they danced, and Ready-to-Halt played his part upon his crutches. Ay, we have our merry-makings, brethren, at which angels find themselves at home. Pilgrims can sing and touch the lively string. When the Lord kills Giant Despair for us we have our Psalms and Te Deums, and we praise the Lord upon the high-sounding cymbals. When we are brought from deep distress our God deserves a song, and he shall have it too. The heathen tune their hymns to great Diana or to Jove, and surely the living God shall not lack for praise. Our hearts are poured out with as great delight and merriment as when the wine vats overflow. We know nothing now of the spirit of wine, for it is evil; but the wine of the Spirit, ah, that is another thing; it filleth the heart with a divine exhilaration which all the dainties of the world can never bestow. The singing pilgrim is a man who has a world of joy within him, and is journeying to another world, where for him all will be joy to a still higher degree. He sings high praises unto God, and blesses his name beyond measure, for he has reason to do so, reason which never slackens or lessens. Oh that we were always as we are sometimes, then would our breath be praise. David remembered his best times. He says, "Thy statutes have been my songs." He recollected that he sang, and sang often. I want some of you who are troubled to-night to rest with us awhile and recollect when you were the Lord’s choristers and sang as heartily as any of the company. You have hanged your harps on the willows. That is a bad thing to do, but it is better to hang your harp on the willows than to break it, for it may be taken down and used again for the Lord’s glory. Jesus, who has a tender heart for mourners, will see you again, and your heart shall rejoice. Think not that the past has devoured all your happiness; hope lives, peace abides, and joy is on the wing. Recall those sweet songs yon loved to sing. Recall them, I say, and find in them arguments for renewed praise. If you cannot graze in the pastures of delight and feed upon new joys, ruminate upon the old ones, and get from them rich nutriment for praise. Think of happier days, and be happier. Listen to the echoes of your former psalms, and begin to sing again. The thing that has been is the thing that shall be. "The Lord hath been mindful of us, he will bless us." The Psalmist bears his testimony that though now he maybe mourning yet he did once sing. I wish that Christians whenever they feel discouraged and doubting would not begin telling everybody, "Oh, I am bowed down," without saying also, "I was not always so. For years I was free as a bird, and did not envy an angel; nor shall I be always sorrowful; I shall wear my plumes again and fill the air with my songs. I am not going to be bowed down always. I have sackcloth on my loins to-day, but I do remember when I was dressed in silken apparel, and rejoiced before the Lord. My sackcloth will not last long. ‘Weeping may endure for a night:’ it is the time for dews. ‘But joy cometh in the morning,’ that is the time for sunlight and for bird-singing, and so it will be with me." Recollect what you used to do, dear friend, in the heyday of your faith; and tell others what you used to do that they may not think you have always been a knight of the rueful countenance. Do not let the Hill Mizar and the Hermonites be quite forgotten. When "deep calleth unto deep," say "I will remember thy former lovingkindnesses, and joys long past, and so will I put my trust in thee." Well may every pilgrim to heaven be a singing pilgrim, because he is getting every day nearer to the land where it is all singing. There are many delights in heaven, but the main thing about heaven is the adoration of God. Oh, if I might once adore with my whole being, I would ask never to do anything else for ever, but to melt away in reverent worship of the blessed God. Oh, what singing that will be, when you will sing your best, your heart made perfect to sing worthily in accord with the plane and theme. Oh for the music which is all harmony and no discord! What music that will be when all the dear voices which have been hushed, which we can hardly think of now without a tear, will all ring out clearly the praises of God, when all the myriad voices that have gone before will join in full chorus when all shall be perfect, and all shall be there, and ail shall praise God for ever. Come, pilgrim, sing, for you are going to sing for ever. Now, rehearse your blessed anthem. Sing unto the Lord now, since you are to sing unto the Lord world without end. "Such songs have power to quiet The restless pulse of care, And come like the benediction That follows after prayer.

And the night shall be filled with music And the cares that infest the day Shall fold their tents, like the Arabs, And as silently steal away." III. Now, I must come to a close, for time admonishes me; and the last head was to be THE SONG BOOK: "Thy statutes have been my songs in the house of my pilgrimage." The Bible is a wonderful book. It serves a thousand purposes in the household of God. I recollect a book my father used to have, entitled "Family Medicine," which was consulted when any of us fell sick with juvenile diseases. The Bible is our book of family medicine. In some houses, the book they most consult is a "Household Guide." The Bible is the best guide for all families. This Book may be consulted in every case, and its oracle will never mislead. You can use it at funerals. There are no such words as those which Paul has written concerning the resurrection of the dead. You can use it for marriages where else find you such holy advice to a wedded pair? You can use it for birthdays. You can use it for a lamp at night. You can use it for a screen by day. It is a universal Book; it is the Book of books, and has furnished material for mountains of books; it is made of what I call bibline, or the essence of books. I am preaching to you to-night as a man without books. I cannot get at any of my books, for they are all packed away; but I have a library here in having this one volume, which is, in fact, a number of books bound together. This one Book is enough to last a man throughout the whole of his life, however diligently he may study it. It seems that David, when he was a pilgrim, used the part which he had of this blessed Book as a song-book. It was nearly all history. What could he find to sing of there? He sang the wars and victories of the God of Israel. You and I have a bigger book than David had; can we say that, as pilgrims, we use this blessed Book for songs? Truly we ought to do so, for this is the book that started us on pilgrimage. The blessed teachings of this Book, sent home by the Holy Spirit, made us flee from the City of Destruction, and made us seek the road that leads to life eternal. We sing about this Book, for it is "perfect, converting the soul." It turned our feet from dangerous ways of folly, sin, and shame. By the lessons of this Book "Grace taught our soul to pray, And made our eyes o'erflow," and therefore do we sing of the gracious statutes of the Lord. We use this Book for a song-book, as pilgrims, because it tells us the way to heaven. We often sing as we come to a fresh spot on the route, and bless God that we find the road to be just as we have read in the way-book, just as. our divine Master said it should be. Well may we sing a song of gratitude for an infallible word. We love this Book because it speaks of other pilgrims who have gone this way. It is a Book full of stories of the worthies of old, of whom it tells us, "Once they were mourning here below, And wet their couch with tears, They wrestled hard, as we do now, With sins, and doubts, and fears." It is very delightful to us to read and know how they conquered, and to learn that all true pilgrims who keep to the high road will conquer too. So we sing of Gideon, and of Barak, of Jephtha, and of David, and, above all, of the great Prince of pilgrims who went that way. We love this Book because it describes the life and death of the Prince of pilgrims, even our Lord Jesus. Many a sweet song we get concerning him, as we rehearse the story of what he did and suffered for us here below, and what he is doing for us now. This Book tells us the privileges of pilgrims, both here and hereafter, and of the care which the Lord of pilgrims shows towards all who seek the better country. Best of all, if better can be than what we have said already, we love this Book because it tells us of the place to which we are going. Oh, how it paints that city, not in many words, but in suggestive similes. How wonderfully it talks to us of our abode! Why, if it said no more than that "they shall be with me where I am, that they may behold my glory," we should know enough of heaven to make our hearts dance for joy. To be with Jesus where he is, to behold his glory, this is bliss pressed down and running over, more than our bosoms can hold. Have you ever seen the heavenly country? Has your eye ever been permitted to rest upon it? "No," says one, "certainly not. ‘Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard.’" A very nice text, brother. Go on with it; go on with it. You may make God say what he does not mean if you quote half a text. He says, "Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him; but God hath revealed them unto us by his Spirit." Hence we know these joys by revelation, and that is the best of knowledge. The eye has not seen; but we have done with seeing with eyes when we deal with spiritual things. Our ears have not heard: these are poor deaf things. At best they only hear mortal sounds; but we have an inward function, faculty, power of hearing without ears. God does not speak in audible tones to his children, and yet he speaks to them, and they hear him. We have a spirit which dispenses with fleshly faculties when it comes to deal with God. He has revealed to us somewhat of the joy of communion with Christ; somewhat of the joy of conquered sin; somewhat of the joy of beholding his face, and praising and blessing his name. We know already somewhat of the joy of being made like him, and one with him; and all this sets our feet on the top of Mount Clear, and puts the telescope to our eye: and if our hand be steady, as, thank God, sometimes it is, we see the city; and we long to enter it. "Thy statutes have been my song in the house of my pilgrimage," because there I read of what is to be my home when pilgrim days are over, and I shall see the Master face to face. Now, dear hearers, do you sing out of this holy Book? A country may be judged by its songs; and so may an individual. Do you sing the song of songs? Are God’s statutes royal music for you? A wise man once said that he would permit anybody to make the laws of a country if he had the making of the ballads, for these kindle the spirit and fashion the character. What do you sing, brother? What do you sing? I leave that question as a heart-searching one what do you sing? Or are you one that never sings at all? Poor soul, how do you live here, and where will you live hereafter? Where must non-singers go? God give you a singing heart, and may you sing unto the Well-beloved a song touching the Well-beloved, and keep on singing it "till the day break and the shadows flee away." God bless you. Amen.

|

|